How the vegetables we consume are turning into ‘Poison on our Plates’

At first glance, the fresh, green vegetables displayed in Accra’s bustling markets look safe and healthy. But what if they were grown using water scooped from drains filled with human waste and garbage?

Across the city, urban farmers are using contaminated wastewater to irrigate vegetables sold to unsuspecting consumers. With Ghana seeing a rise in cholera infections, this practice poses a silent but deadly risk to public health.

At a small vegetable farm near a heavily polluted drain in Accra, 49-year-old Peter Kwoffie Arhin bends over a row of leafy greens, carefully watering them with a can. The water he uses comes straight from the stagnant drain beside his farm, murky, dark, and filled with floating debris.

He knows the water is unsafe, but he says he has no other choice.

“For over two decades, this is how we’ve been farming here. If we don’t water the crops, they won’t grow, and we won’t make any money,” Kwoffie explains.

Like him, 35-year-old Abdullah Hussein relies on the same contaminated water for his lettuce farm. His crops are just days away from being harvested, yet every morning, he scoops up the wastewater and sprinkles it over the plants.

They are not alone. Across Accra and other urban farming communities, thousands of vegetable growers depend on water from gutters, drains, and even open sewers to keep their crops alive. Limited access to clean irrigation sources forces them to use the cheapest and most available alternative, one that remains hidden from consumers.

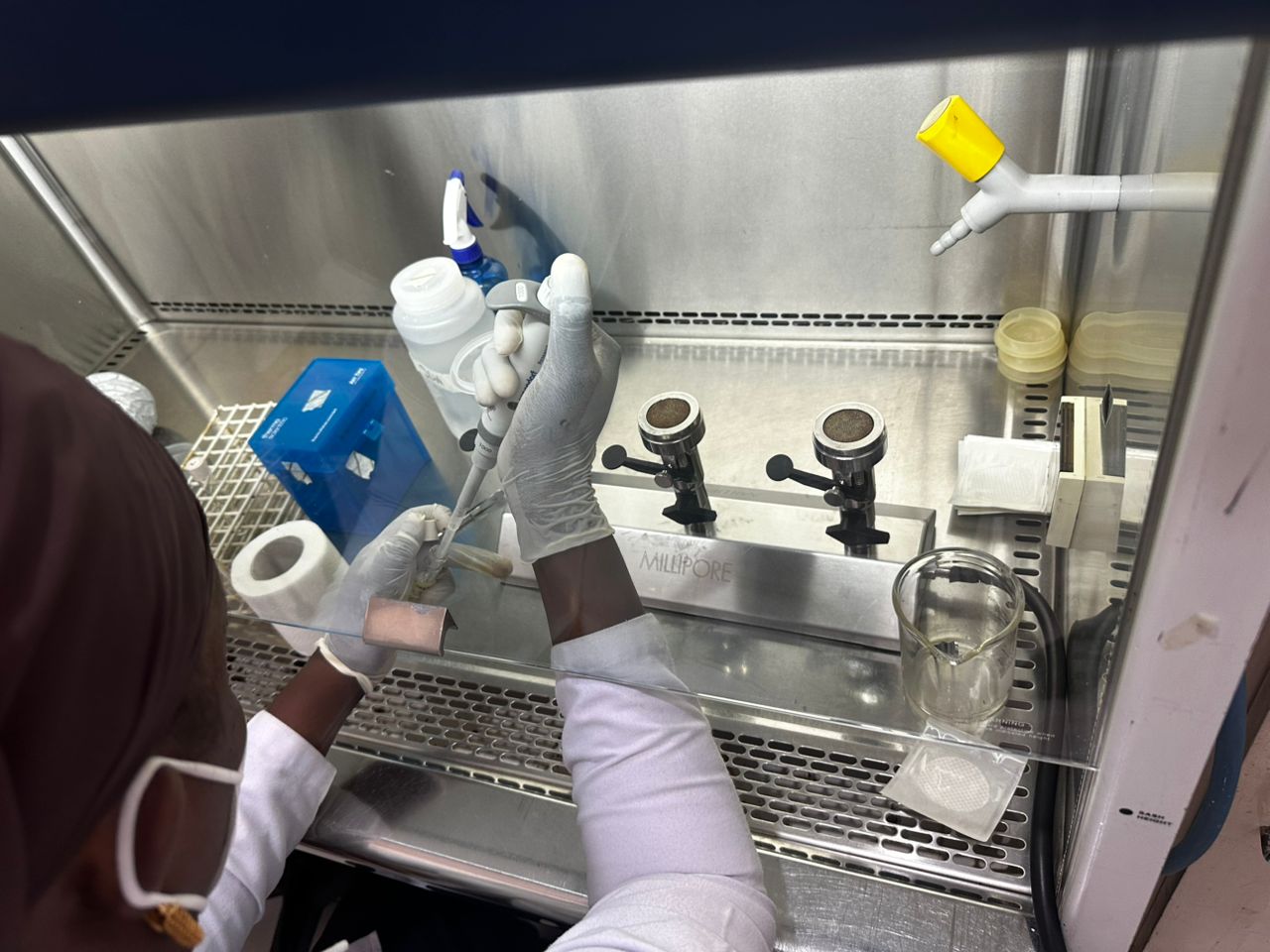

To understand the level of risk, we visited the Water Research Institute’s Microbiology Lab in Accra. Scientists there agreed to test water samples collected directly from the farm sites.

At the drain, some farmers had already connected pumps to extract water for irrigation. The stench was overwhelming, and the water was visibly contaminated with waste. Samples were carefully taken and transported to the lab for analysis.

After 18 hours, the results were in.

The Findings Were Alarming.

“The tests showed heavy bacterial contamination, including E. coli and other fecal bacteria,” a scientist at the lab revealed. “This means the water is carrying disease-causing pathogens, including those responsible for cholera, typhoid, and severe diarrhea.”

Mohammed Bello – Technical officer, Water Research Institute said.

These bacteria don’t just stay in the water. When vegetables are irrigated with contaminated water, the pathogens cling to the leaves. If the vegetables are not properly washed and disinfected before consumption, the bacteria can be ingested, leading to serious illness.

At Malata Market, one of Accra’s busiest food hubs, traders proudly display fresh produce lettuce, cabbage, spring onions, and carrots. Shoppers, unaware of where these vegetables come from, pick up bundles, bargaining for the best price.

But beneath the freshness lies a hidden risk.

Professor Richmond Nii Okai Aryeetey, a public health expert, warns that eating contaminated vegetables can have severe consequences.

“These vegetables are often eaten raw in salads or lightly cooked in soups. If they are contaminated, they become a direct pathway for disease,” he says.

Ghana is already feeling the effects. The Ghana Health Service has reported a rise in cholera cases, with 14 deaths recorded in the Central Region alone. Hospitals are treating more cases of severe diarrhea and dehydration, a warning sign of a larger public health crisis.

Despite the known dangers, wastewater irrigation persists. Farmers say they are trapped between survival and safety.

“We know it’s not good, but what else can we do? Clean water is expensive, and no one is giving us an alternative,” says Abdulai Salifu, another vegetable farmer.

Regulatory agencies have struggled to stop the practice. While food safety laws exist, enforcement is weak, and authorities often turn a blind eye.

Experts say the solution lies in providing safe irrigation alternatives and educating farmers about the risks. Some initiatives, like wastewater treatment facilities for agricultural use, have been introduced in small pilot projects. However, widespread change has been slow.