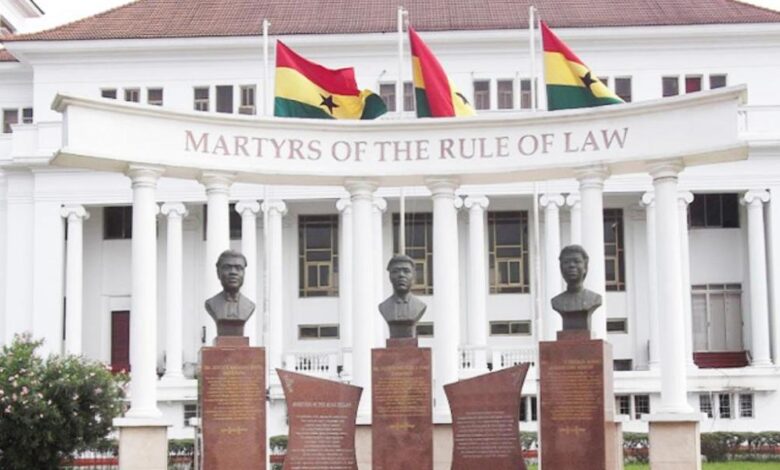

Supreme Court Ruling Expands Disclosure Rights for Accused Persons in Criminal Trials

Ghana’s Supreme Court has issued a landmark ruling that enhances the rights of accused persons to evidence held by the prosecution, following a recent decision in The Republic v. Adu-Boahene case, as outlined by the Deputy Attorney General.

Under the revised legal framework, prosecutors must now disclose all material obtained in the course of investigations, whether it supports guilt or could potentially exonerate the accused, before a trial begins.

This requirement strengthens the constitutional right to a fair trial and defence.

Previously, for an accused person to access further disclosures, two criteria needed to be met: evidence had to be both relevant to guilt or innocence and in the possession of investigators. However, the Supreme Court’s decision removes the so-called “relevance rule.”

Going forward, accused persons need only demonstrate that the requested evidence was gathered by investigators during the investigation related to the charges they face; it is no longer necessary to prove its relevance at the requests stage, as that will be determined in court during trial.

The ruling also provides a safeguard: while the accused can now ask the court to order further disclosures if the prosecutor appears unwilling to volunteer all materials, this process cannot be used to delay proceedings or force the prosecutor to act as defence counsel.

There remain clear limits to disclosure requests.

Read What Deputy Attorney General Wrote:

NEW LAW ALERT

The law requires a prosecutor to facilitate an accused person’s defence. So, he is to disclose to the accused person every evidence which investigators found during investigations. So, before a trial begins, a prosecutor must file such disclosures.

The disclosures must include evidence which will show that the accused person is guilty. But that’s not all. It must also include evidence which the prosecutor knows or believes can help the accused person to show that she is not guilty.

Because the prosecutor cannot be trusted to voluntarily file every evidence (especially the one that he knows can show that the accused person is not guilty), the law allows the accused person to ask the court to direct the prosecutor to make further disclosures.

However, the accused person is not allowed to use the opportunity for further disclosures as a ploy to delay the trial or convert the prosecutor into defence counsel. So, there are limits to what the accused person can get from seeking further disclosures.

Before last week, October 29, when the Supreme Court decided The Republic v Adu-Boahene case, there were, by case law and practice direction, two criteria for determining what an accused person may get through further disclosures.

The first criterion is the RELEVANCE Rule. This says that an accused person can, by way of further disclosures, get from the prosecutor only evidence which has a bearing on proving that she is guilty or not guilty. If it is not relevant, it wont be disclosed.

The second is the POSSESSION rule. It says that the evidence which the accused person asks for must be evidence which came into the hands of investigators during the investigation of the offences which the accused person is charged with.

The Adu-Boahene case has changed this law: The RELEVANCE rule no longer applies. That is to say that an accused person doesn’t have to show that the evidence, disclosure of which she seeks, is relevant to proving anything. Relevance will be determined at the trial.

She only has to concern herself with the POSSESSION rule. That is – she just has to show that the evidence she seeks came into the investigators’ hands during the investigations of the offence which she is charged with.